Chapter: The Cell Cycle

Cell Division

Mitosis is the process of cell division in which one cell divides to form two genetically identical daughter cells. In unicellular organisms, mitosis functions as reproduction: the cell copies its genetic material and splits, producing two identical offspring.

In multicellular organisms, cell division serves two essential roles. First, it enables growth and development. Beginning as a single fertilized egg, repeated cycles of mitosis produce the trillions of cells that form a complex organism. Second, it allows for repair and renewal, replacing old, worn-out, or damaged cells.

Cells in the human body are constantly turning over. For example, many skin cells are replaced roughly every month. Most cells do not last a lifetime, though some—such as many nerve cells—can persist for decades. Other tissues, including bone, undergo continual renewal. On average, a large proportion of the body’s cells are replaced over several years. This ongoing biological turnover highlights that the body is a dynamic, constantly renewing system.

A defining characteristic of life is the ability to reproduce. In unicellular organisms, mitosis produces new individuals. In multicellular organisms, cell division supports growth, maintenance, and tissue repair. In organisms that reproduce sexually, however, a different process is required: meiosis. Meiosis halves the genetic material to produce gametes, which later combine during fertilization to form a zygote.

Cell Division. Source

Binary Fission

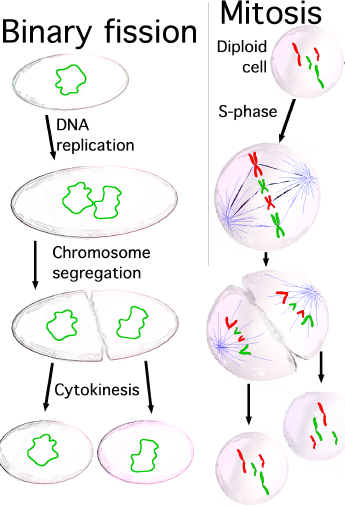

Before examining mitosis, it is helpful to understand how prokaryotic cells divide. Prokaryotes reproduce through binary fission, a term meaning “splitting in half.” This process is simpler than mitosis because prokaryotic cells lack a nucleus.

During binary fission, the cell’s single circular chromosome replicates. The cell then elongates, and the two DNA copies move apart. Next, the plasma membrane and cell wall pinch inward, ultimately dividing the cell into two genetically identical daughter cells.

Binary fission is an asexual process that produces exact clones. Genetic variation arises only through mutations that occur during DNA replication.

Binary Fission. Source

The Eukaryotic Cell Cycle

In eukaryotic cells, division occurs as part of a larger sequence called the cell cycle, which has three main stages: interphase, mitosis, and cytokinesis. Most of a cell’s life is spent in interphase, when the cell grows, carries out normal metabolic functions, and duplicates its chromosomes. Mitosis follows, during which the nucleus divides and the duplicated chromosomes are separated into two nuclei. After the nucleus divides, the cell completes division through cytokinesis, in which the cytoplasm splits, producing two daughter cells.

The Eukaryotic Cell Cycle. Source

Interphase

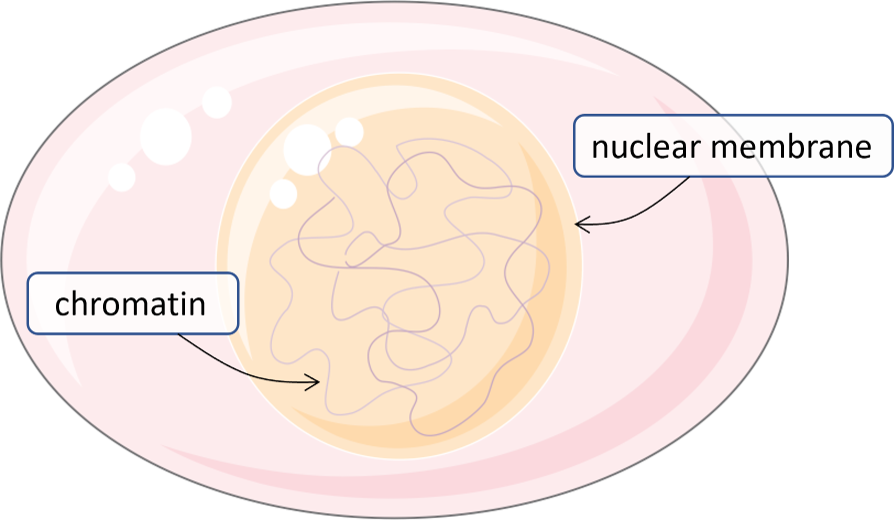

Interphase is a stage of the cell cycle during which the cell performs its normal functions and replicates its chromosomes. In eukaryotic cells, interphase is easily recognized because the chromosomes are relaxed and not distinctly visible under a compound microscope. This contrasts with mitosis, when chromosomes are condensed and clearly visible.

Interphase is subdivided into three phases: G1, S, and G2.

Eukaryotic cell during DNA Synthesis. Source.

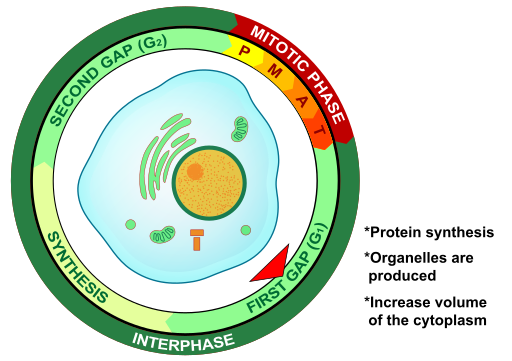

G1 phase of Interphase

The G1 phase, or “Gap 1,” occurs immediately after cell division. During this phase, the cell grows and synthesizes proteins necessary for DNA replication. It is a period between cell division and chromosome duplication.

G1 Phase of Interphase. Source.

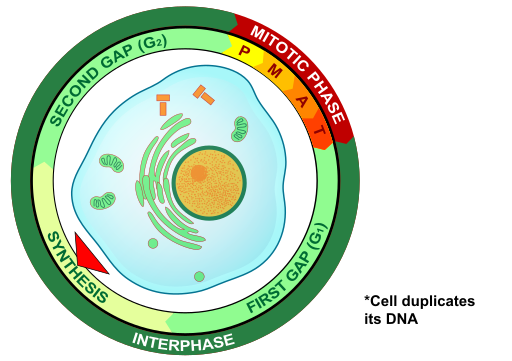

S Phase of Interphase

The S phase, or synthesis phase, is when DNA replication occurs. During this stage, each chromosome is copied. However, the DNA at this point is not tightly packed. Instead, it exists in a relaxed, threadlike form called chromatin, which resembles strands of spaghetti under a microscope and is difficult to distinguish clearly.

S phase of Interphase. Source.

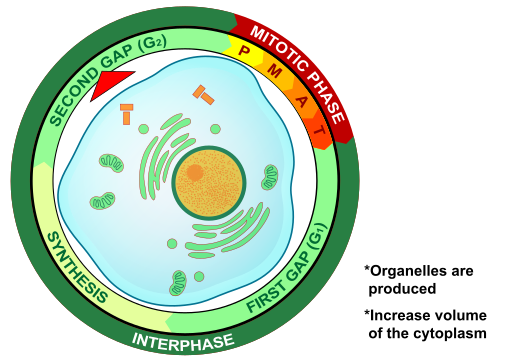

G2 Phase of Interphase

The G2 phase follows DNA replication. During G2, the chromosomes have been duplicated but remain uncondensed. The cell continues to grow and prepares for mitosis by producing proteins and organelles required for cell division. Growth occurs throughout all stages of interphase.

G2 phase of Interphase. Source

The Structure of Chromosomes During Mitosis

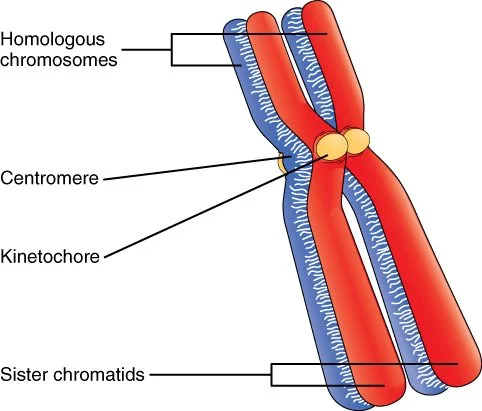

Mitosis focuses on the behavior of chromosomes within the nucleus. At the end of interphase, chromatin condenses into distinct chromosomes that become visible under a microscope. These condensed chromosomes often appear X-shaped.

Each X-shaped chromosome consists of two identical copies of DNA known as sister chromatids. The two sister chromatids are joined at a region called the centromere. One can think of each sister chromatid as a long strand, with the centromere representing the point where the identical copies are held together. Together, the pair forms a single duplicated chromosome.

In diploid eukaryotic cells, chromosomes also exist as homologous pairs. Homologous chromosomes are two separate chromosomes—one inherited from each parent—that carry the same genes arranged in the same order. They are similar in size, shape, and genetic content but are not identical. For example, they may contain different versions (alleles) of the same gene. Importantly, homologous chromosomes pair and separate during meiosis, not mitosis. In mitosis, it is the sister chromatids of each duplicated chromosome that are pulled apart.

Attached to the centromere is a protein structure called the kinetochore. Spindle fibers, composed of microtubules, attach to the kinetochores during mitosis. Although spindle fibers are difficult to observe directly, their function is essential: they pull sister chromatids apart, ensuring each daughter cell receives an identical set of chromosomes.

Homologous Pair of Chromosomes. Source

Cellular Structures Involved in Mitosis

When viewing the entire cell, chromosomes are enclosed within the cell membrane and, initially, the nuclear envelope. Spindle fibers extend from structures called centrioles, which occur in pairs. Each centriole pair is positioned at opposite ends of the cell.

The centrioles serve as anchoring points for the spindle fibers. As mitosis progresses, these fibers function like mechanical winches, shortening to pull sister chromatids apart. The coordinated activity of spindle fibers and centrioles ensures that each daughter cell receives an identical set of chromosomes.

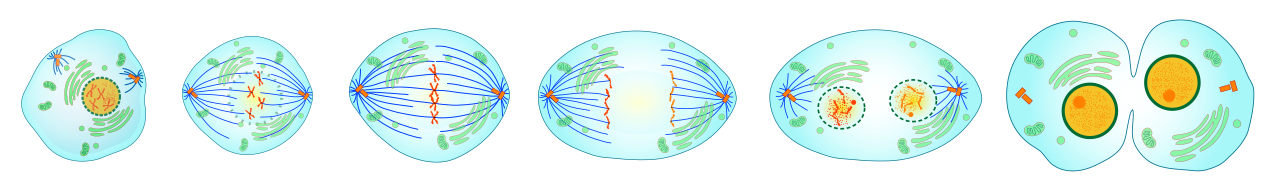

The Phases of Mitosis

Although mitosis is described in distinct stages, it is a continuous process. Each phase transitions smoothly into the next. For clarity and study purposes, mitosis is divided into five phases: prophase, prometaphase, metaphase, anaphase, and telophase.

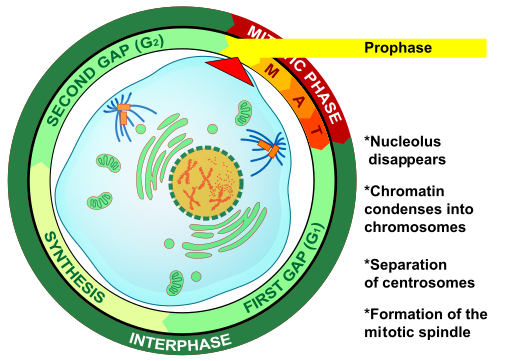

Prophase of Mitosis

Prophase marks the beginning of mitosis. During this phase, chromatin condenses into visible chromosomes. The nuclear envelope begins to break down, though the precise mechanisms controlling this disassembly remain an area of scientific investigation. Meanwhile, spindle fibers begin to form and extend outward from the centrioles located at opposite sides of the cell.

Prophase of Mitosis. Source

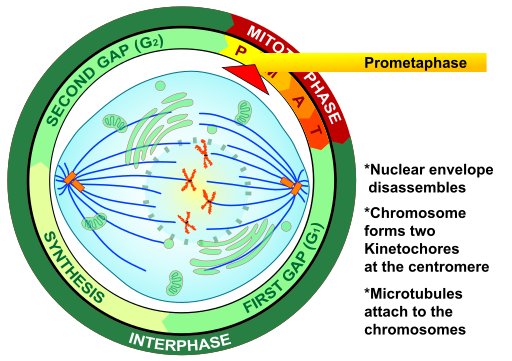

Prometaphase

Prometaphase, sometimes referred to as late prophase, is characterized by the complete breakdown of the nuclear envelope. With the nucleus no longer intact, spindle fibers can interact directly with the chromosomes. The chromosomes begin moving toward the center of the cell as spindle fibers attach to their kinetochores.

Prometaphase of Mitosis. Source

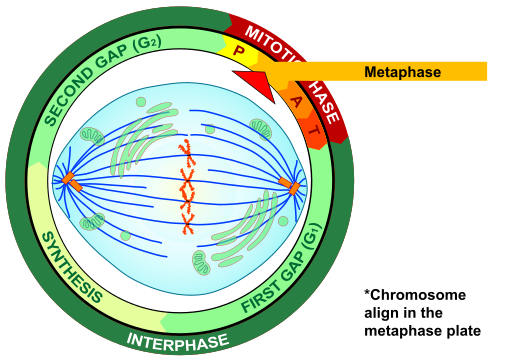

Metaphase

During metaphase, the chromosomes align along the center of the cell in a formation known as the metaphase plate. The centrioles are positioned at opposite poles, and spindle fibers are fully attached to the kinetochores of each sister chromatid. The cell ensures that each chromosome is properly aligned before proceeding, as accurate separation is critical to maintaining genetic stability.

Metaphase of Mitosis. Source

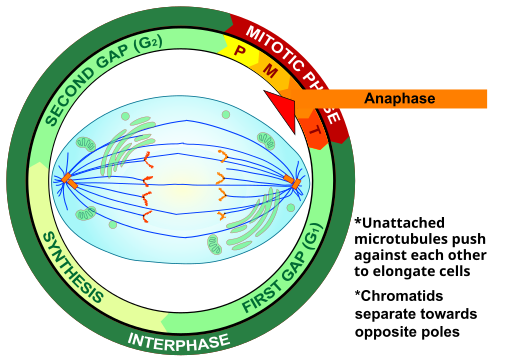

Anaphase

Anaphase begins when the sister chromatids separate at the centromere. Once separated, each chromatid is considered an individual daughter chromosome. The spindle fibers shorten, pulling the daughter chromosomes toward opposite poles of the cell. This movement ensures that identical genetic information is distributed to each side.

Anaphase of Mitosis. Source

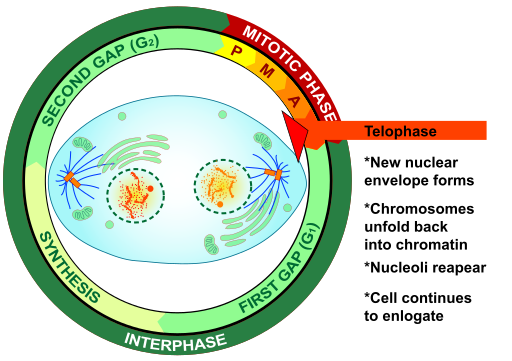

Telophase

Telophase marks the final stage of mitosis. Nuclear envelopes begin to reform around each set of daughter chromosomes, though the mechanisms underlying this reassembly are not fully understood. The chromosomes begin to uncoil, returning to their less condensed chromatin state. Spindle fibers disassemble, and the two developing daughter cells move further apart.

Telophase of Mitosis. Source

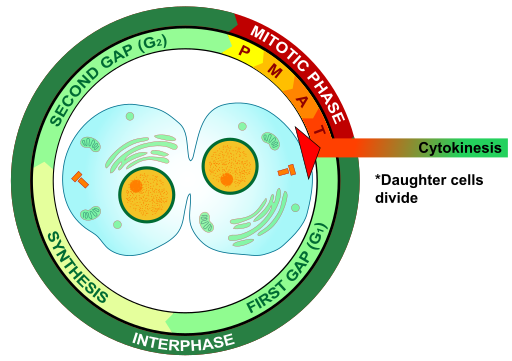

Cytokinesis

Cytokinesis completes cell division. Although often discussed alongside mitosis, it is technically a separate process because mitosis refers specifically to the division of the nucleus and chromosomes. Cytokinesis involves division of the cytoplasm.

Cytokinesis. Source

In animal cells, cytokinesis occurs through the formation of a cleavage furrow. The plasma membrane constricts inward, eventually pinching the cell into two separate daughter cells. In plant cells, cytokinesis differs due to the presence of a rigid cell wall. Instead of pinching inward, plant cells form a cell plate at the center of the cell. This structure develops into a new cell wall that separates the two daughter cells.

Through the coordinated processes of mitosis and cytokinesis, eukaryotic organisms grow, repair tissues, and maintain life. Cell division ensures continuity of genetic information and sustains the dynamic renewal that characterizes living systems.